Here’s our third installment of our How to Grow Chinese Vegetables series: how to grow Chinese eggplant.

We actually prefer Chinese (or Japanese) eggplants over regular globe eggplants. Not only is the skin thinner and less tough, they also have fewer seeds, making them sweeter and less bitter!

If you’re new to this series, it’s a collaboration between The Woks of Life and Choy Division, a regenerative Asian vegetable and herb farm in the Hudson Valley.

We’ll share farmer Christina Chan’s knowledge on growing Chinese eggplant, as well as what we learned this past season growing them from seed in our own garden!

About Chinese & Japanese Eggplant

Eggplants are in the Solanceae family—the nightshades—and are related to potatoes, peppers, and tomatoes. Like peppers and tomatoes, eggplants love sun and heat, and can’t tolerate frost.

Both Chinese and Japanese eggplants have a longer, more slender shape than the Italian or American eggplants you may be more familiar with.

As I mentioned already, they have fewer, smaller seeds, and thinner skin, which makes them a lot more pleasant to eat! While you may peel your eggplant normally, we never peel Chinese eggplants, because the skin is thin and tender.

(We share our favorite eggplant recipes at the bottom of the post.)

If you’re wondering about the differences between Chinese and Japanese eggplants, the main one is that the Japanese varieties are usually darker purple—sometimes almost black. Chinese eggplants, on the other hand, are usually paler purple.

In the kitchen, though, the two types are basically interchangeable. If a recipe calls for Chinese eggplant, you can use Japanese eggplant, and vice versa.

That said, there are other Asian varieties of eggplant that have different shapes and colors—some are small and round, while others aren’t even purple, but green! We’ll cover different eggplant varieties in the next section.

Varieties You Can Grow

Here’s Christina’s list of eggplant varieties!

- Ping Tung, Ping Tung Long (Taiwanese): long, slender lilac colored eggplants; the quintessential “Asian eggplant.”

- Orient Express and Asian Delite: despite their somewhat problematic names, these are commonly grown varieties of long Asian eggplant.

- Kamo: a Japanese heirloom variety with a flat bottom, round shape, and dense flesh that’s great for cooking.

- Thai Round: A variety of small, round green eggplant popular in Thailand, Vietnam, and India. Needs a long hot season, and takes a while to start fruiting. Harvest at golf ball size.

We planted a variety called Eggplant Charming, from Asiangarden2table.com. The seeds were a couple seasons old, so I don’t think they offer that particular variety anymore, but you can check out their website to see what’s available!

Ideal Growing Conditions for Eggplant

Climate/Weather:

While eggplants are grown as annual crops in North America, they actually grow wild in South Asia as perennial plants! That should give you an indication of the conditions they like.

Eggplants need warm soil and hot weather, so don’t put them into the ground until well after the last threat of frost has passed. They’re also susceptible to wide temperature swings, with overnight temperatures below 55°F (13°C) and hot days above 95°F (35°C) causing poor fruiting.

Generally, this means it’s better to plant them out a bit later rather than earlier to be safe, when nighttime temperatures are warmer. Eggplants grow faster when temperatures are between 70-85°F (21-29°C). Planting too early may affect the vigor of the adult plant.

As the summer gets hotter, the plants will put on more growth. They thrive in the heat, but if temperatures exceed 95°F, they may drop their blossoms. (Water stress and cold stress can also cause eggplant blossom drop.)

Sunlight:

Like peppers and tomatoes, eggplants need full sun! Place them in a spot that will get 6-8 hours of direct sunlight per day. The more the better!

Soil Conditions:

Eggplant grows best in loamy soil (balanced between sand, clay, and silt), which is well-draining but also moisture-retentive. They are also heavy feeders, so giving them organic matter (a layer of compost on top of the soil) will help them grow strong and healthy. Mulching with compost will also help retain moisture in the soil!

If growing eggplant in a pot, a dark-colored container will absorb more sunlight and keep the soil warm and toasty. Raised beds are also ideal for growing eggplant, as they warm up quicker than the ground.

Watering:

Keep your eggplants well-watered so that the soil is consistently moist but not sodden. This is especially important while the plants are fruiting!

Spacing:

Christina suggests spacing plants at least 18 inches apart. Eggplant needs a lot of nutrients, and tight spacing will cause them to compete with each other and struggle to draw enough nutrients from the soil.

Days to Maturity:

They take an average of 50-65 days to mature after transplanting, depending on the variety.

We sowed our eggplant seeds in late March, planted them out into the garden in late-May, and began harvesting eggplants in the third week of July. They have been fruiting since then, and we’re well into August!

How to Grow Eggplants from Seed

Because they cannot tolerate cold temperatures, eggplants are best started indoors and then transplanted outside when it’s warm. Direct seeding is not recommended.

Start seeds indoors 6-8 weeks before the last frost, and plant outside well after the last frost has passed.

In a seed tray with peat-free potting soil or garden compost, sow seeds ¼ inch (0.6cm) deep. Water the seed tray well, and place on a heated mat. Eggplant seeds need warm soil (80-90°F) to germinate. You can also cover the trays with a clear plastic lid (we use old plastic salad boxes that we rinse out) to increase the humidity in the tray and promote germination.

When the seedlings appear, remove any plastic lids, and remove the tray from the heated mat. Place the seedlings in a well-lit area. They need tons of light, so a greenhouse or an indoor space with grow lights is ideal. If they don’t get enough light at this stage, you’ll end up with weak growth.

As the seedlings grow larger, you can pot them on into small individual pots to allow them more room to grow.

When all danger of frost has passed, and the ground has warmed (soil temperatures above 70-75°F), you can harden them off and transplant them outside.

To harden off the plants, place the seedlings (still in their trays) in a sheltered area outside to acclimate to the elements for 1-2 weeks.

To transplant, tease out each seedling with as much of its root ball intact as possible, plant into the ground 18 inches (46cm) apart, and water in well.

As they grow, stake the plants or use a cage to keep them upright. If growing eggplant in containers, stake the stems before the fruit forms.

Harvesting & Storing

When the eggplant has reached appropriate size (whatever that may be for your given variety), simply give it a firm yank, and it should come off the plant. You can also use a knife or shears to clip the stem.

The skin should be smooth and shiny. If it has become matte or starts to show yellowing, it is likely no longer good to eat and is best removed from the plant and composted.

You can harvest from one plant all summer long, until the plant dies. It will continue to put on fruit, and the more you pick, the more it will produce.

Keep eggplants in a plastic produce bag in the the crisper drawer of the fridge (storing it without a bag will cause it outside to wrinkle faster), and use within 1 week.

Pest Management

Here are Christina’s tips on eggplant pest management!

The main pests affecting eggplant in the Northeastern U.S. include the Colorado Potato Beetle and flea beetles. There may be different/additional pests in your region, so check out your local cooperative extension for more info.

Eggplant flea beetles look the same as the brassica flea beetles that attacked our napa cabbage, but they’re a separate species that feeds on eggplant. They will create similar looking masses of tiny holes in the leaves.

Colorado potato beetles are large and easy to spot. Both juvenile and adult forms will cause significant damage to your crop and can completely decimate it if left unmanaged. As you can guess, they are a major pest to potatoes as well as tomatoes.

If you are growing all of these crops, be sure to check all of them for this insect. Adults can be spotted first and will proceed to lay clusters of orange eggs on the underside of leaves.

The most effective way to manage these pests is through prevention. Covering your eggplant immediately after planting using row covers will keep almost all of them out. They will also enjoy the extra warmth!

If unable to cover your plants (or you find potato beetles after you’ve removed it), the best method is manual control. If you’re not squeamish, you can just squish all the bugs and eggs.

Christina says, “Sometimes there are so many that I bring a bucket of soapy water and knock them into the bucket. Just water won’t kill them—make sure to add dish soap.”

Checking once or twice weekly until your plants have set fruit should keep the majority of them at bay.

questions about how to manage weeds?

Check out our section on weeding in our How to Grow Bok Choy post.

Eggplant Origins and Ancestral Stories

Eggplant is indigenous to a vast area from northeast India and Burma to Northern Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Southwest China. Wild plants can still be found in these locations, and are actually perennials!

In its native Asia, eggplant has been cultivated and bred for centuries, resulting in many unique cultivars.

The earliest written record of the eggplant in Chinese literature is this statement of Han Dynasty Poet Wang Bao in his work Tong Yue from 59 BC: “In the second month of the year, the Spring Equinox … separate and transplant seedlings of eggplant and scallion.”

Later Chinese records describe the specific changes that Chinese agronomists deliberately bred into domesticated eggplant. Through selective breeding, small, round, green fruit transformed into larger, long-necked fruit with purple skin.

Fascinatingly, the search for superior flavor is also documented in such records, as Chinese botanists endeavored to remove bitterness from the eggplant.

The contemporary Chinese eggplant variety most common in the U.S. is the Ping Tung Eggplant, named after Pingtung, Taiwan—its city of origin. It is favored for its robust production of fruit, weather hardiness, and relative disease resistance. When cooked, the flesh has a creamy texture that is never bitter.

Beyond culinary uses, aristocratic women in Southeast Asian and Oceanic cultures used dark eggplant skins to make black dye, which they used to “stain their teeth to a black luster.” In Japan, this is called ohaguro.

Our Favorite Eggplant Recipes

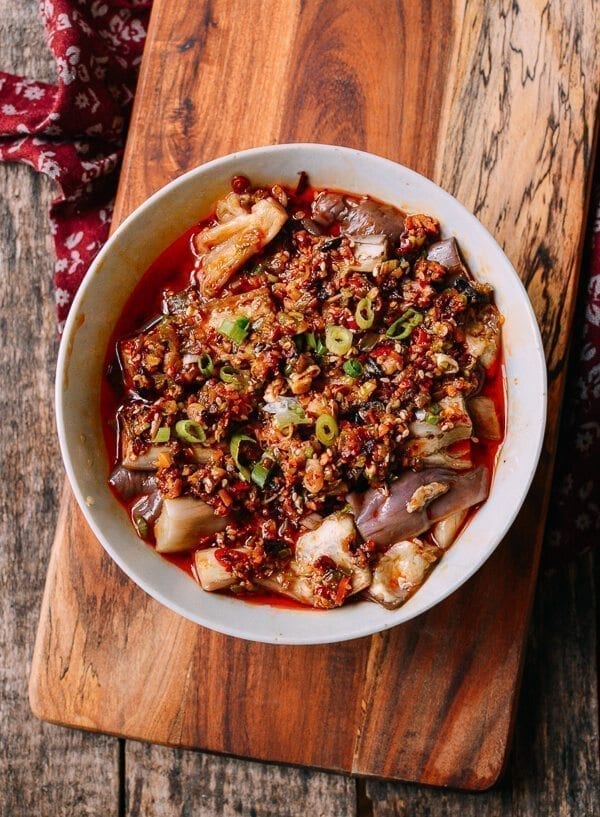

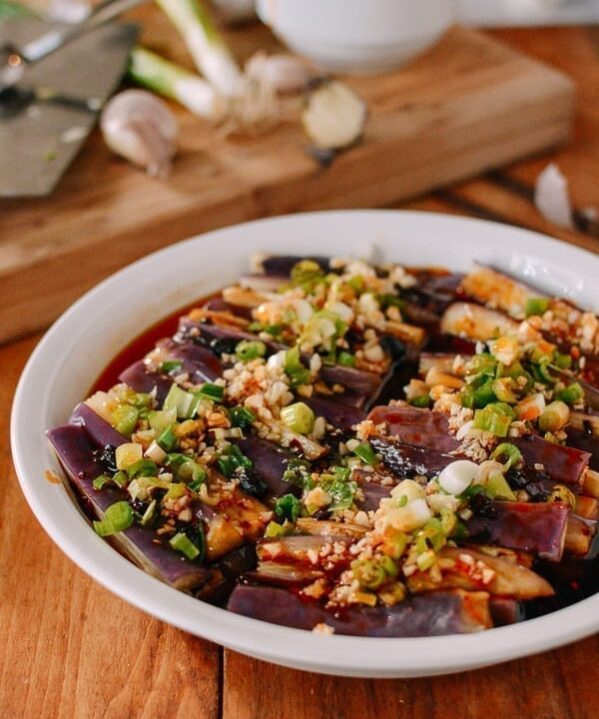

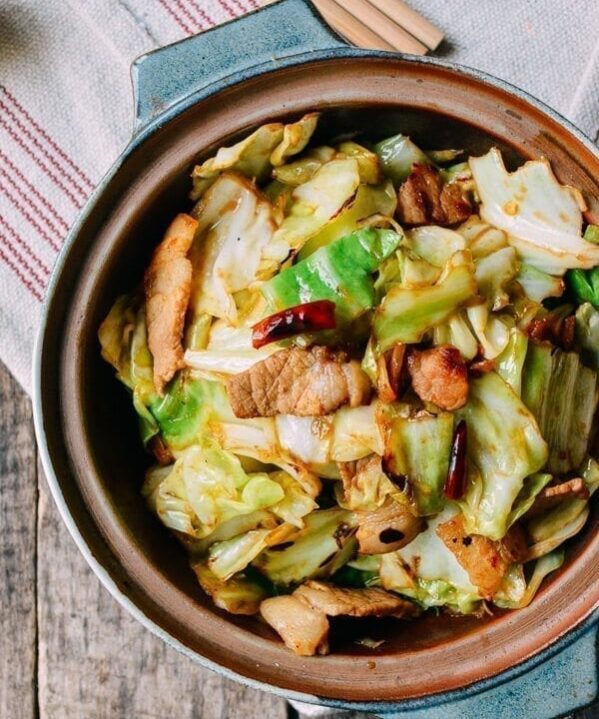

We have 5 eggplant plants, so our garden is bursting with them right now! Here are some of our favorite recipes that we’re using them in:

- Mapo Eggplant

- Eggplant with Thai Basil & Chicken

- Eggplant with Garlic Sauce

- Eggplant “Unagi”

- Di San Xian (“Three Earthly Bounties”)

- Steamed Chinese Eggplant with Spicy Lao Gan Ma

- Steamed Hunan-Style Eggplant

- Chinese Stuffed Eggplant

- Cantonese Eggplant Casserole

- Pasta alla Norma with Roasted Eggplant & Tomatoes

- Roasted Ratatouille Pasta

Hope you enjoyed this gardening post, and that this past season of learnings helps you grow your own Chinese eggplant next summer. Happy gardening and cooking!